Image source: Energy Service Bristol

The good people of Bristol have been striving for a greener environment for at least fifty years. Little wonder then that the city’s coronation as European Green Capital in 2015 was cause for a good deal of well-deserved celebration.

In particular, Bristol impressed the European jury with its investment plans for transport and energy. €500 million was pledged for transport improvements and €300 million to reach targets for using renewable fuels and achieving greater energy efficiency. The city’s Sustainable Energy Action Plan commits it to major reductions in carbon dioxide emissions by 2050 (to just 20% of 2005 levels). At the forefront of these efforts is the policy of building urban Combined Heat and Power plants (CHPs).

How the Bristol Heat Network works

Combined heat and power plants are essentially small power stations. Because they are located in urban areas, it becomes feasible to supply their heat through networks of pipes to local homes, shops and offices. Most of them run on either gas or biomass. Electricity generated can be sold onto the National Grid but can theoretically backup local power supply too.

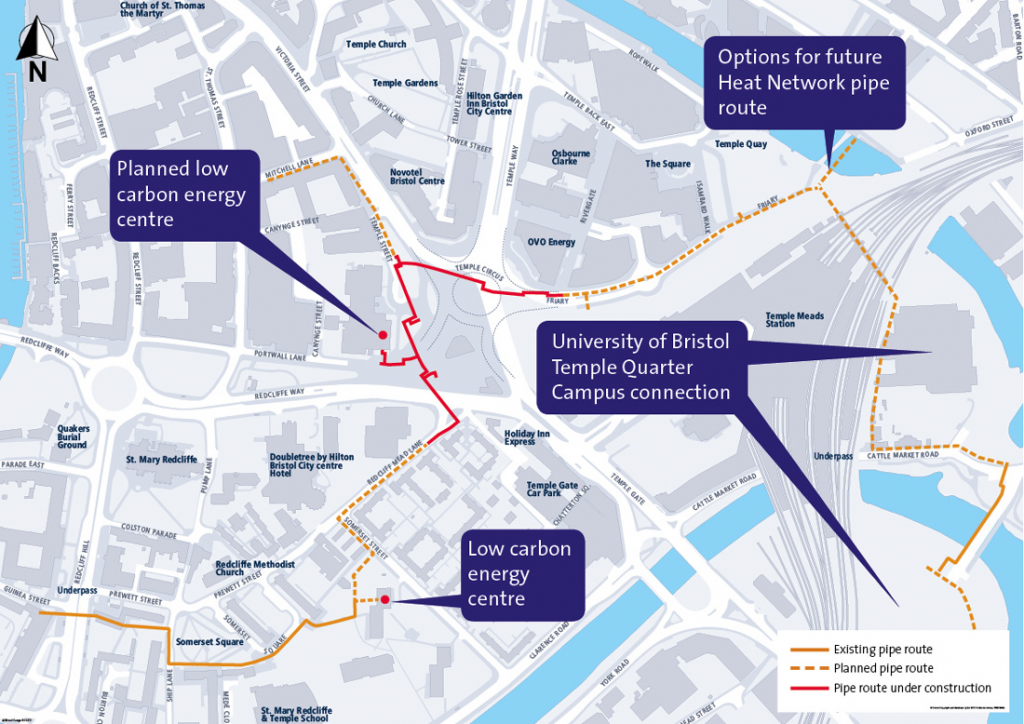

The council already uses its own network of pipes, supplying over a thousand social housing properties and is partnering roll-outs of new networks across the city.

Five blocks in Hartcliffe are already connected to a 360kW wood pellet boiler and the first part of the Temple & Redcliffe heat network is already supplying 13 blocks. At the centre of the Redcliffe network is a 1MW biomass boiler and another 3.6MW is supplied by gas boilers. The new Castle Park View housing development of 375 homes will be connected to the council network when completed in 2022.

Bristol City Council is mandating that all new developments in their designated heat priority areas must connect to a heat network whenever it is technically feasible to do so. It’s hoped that disruption from building the new networks will be minimised by coordinating road works with new road constructions, fibre-optic broadband installations, the MetroBus redevelopment and the Arena project.

Although the CHPs are still burning carbon-based fuels that create carbon dioxide, their overall energy efficiency is improved, which represents a CO2 reduction. Fuel efficiency should also translate into lower energy bills for the end consumers. In time, the council says it hopes to improve the renewable credentials of the fuels or link some to green energy sources such as solar panels.

Why do we need heat networks?

Although benefits to Bristol’s consumers and ratepayers are promised, the main thrust of the plan is to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. It is generally accepted that reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide will mitigate global warming and climate change.

Heat networks may have other benefits. For example, they remove the need for new buildings to accommodate their own HVAC boilers. Calculations suggest that centralised CHPs will produce less pollution overall than the individual private boilers they replace.

Some of the new energy centres will be installed inside existing buildings. For example, there is now a 1MW wood pellet boiler operating in Broughton House. In the future, CHPs might even be housed in mobile shipping containers.

Concerns about CHPs

Not everyone is convinced about the benefits of CHPs and heat networks.Criticism focuses on three main aspects; the validity of efficiency and carbon reduction claims, the threat they pose to local environments and the problems in administering them.

Some have pointed out that the idea of local power generation is at odds with the policy of encouraging electric cars. The electric car effectively relocates power generation, and therefore air pollution, to power stations at a safe distance from where most of us live and work. CHPs do the reverse; they bring power generation, and therefore pollution, back into the city.

Although they may deliver an overall decrease in air pollution, that isn’t necessarily a comfort if you live down-wind of one. Air quality experiments conducted in London and elsewhere seem to indicate these dangers can be significant.

Others have challenged assumptions about the carbon-neutrality of the wood chip and other biomass fuels that many of them burn. They also point out that heat-generating capacity is wasted in summer months and that unlike HVAC systems, heat networks cannot share resources with the cooling systems that larger buildings often need.

Administrative objections include civil liberty concerns about the rights of home-owners, businesses or tenants to opt out. It isn’t clear if households can legally be denied the right to choose their own utility providers, but calculations and projections usually assume everyone will be serviced by the scheme.

Each privately run network also needs to bill and service the buildings it supplies. In contrast, regional energy suppliers benefit from economies of scale.

Other concerns include the noise and traffic that will be generated by each CHP. Bristol City Council is confident that these problems can be overcome by modern sound insulation and by restricting fuel deliveries to standard weekday work hours.

Bristol’s long term plans for heat networks

New heat pipelines will be developed and extended in phases scheduled over the next 20 years and beyond. In all probability, most of Bristol will eventually become a part of a network.

Currently, most projects are connected with social housing provision, something Bristol Council has pledged to extend and improve. However, inquiries are also invited from private building owners and developers. In addition to the environmental and cost incentives to connect to one of the new heat networks, developers and existing businesses may find it makes it a great deal easier to comply with the increasing regulatory requirements to make buildings and businesses more energy efficient.

The council is also looking at the feasibility of installing heat exchangers in the floating harbour to recover heat that can be fed into the project.